Why we should all stan Lawrence from ‘Insecure’: exploring the complexity of Black masculinity

Sayou Cooper

For several Sundays last autumn, my nights were preoccupied by a weekly dosage of HBO’s critically acclaimed series, Insecure.

These viewings were immediately followed by a scroll through Twitter to see what my people, otherwise known to the general public as ‘Black Twitter’, were saying. Through a slew of memes and humorous commentary, I was able to debrief alongside other Black folks who shared similar contemplations and attachment to the show’s characters.

Issa Rae began working on the pilot in 2013 with co-creator Larry Wilmore, spawning the idea from her popular and indie web series, Awkward Black Girl. Insecure originally premiered on October 9, 2016, through HBO which in recent years has become the leading cable platform for Black creatives, with I May Destroy You and Random Acts of Flyness also on its roster.

With the premiere of Season 1, the show garnered both critical acclaim and routined comparisons. In an interview for Vulture, Rae noted how the comparisons brought up frustration.

“Season 1, I was more frustrated with the Girls comparisons. I wanted to stand on my own two feet because I had been continuously compared to Lena Dunham since my Awkward Black Girl days, and, love her, respect her, but as a creative, when you’re coming out, you want to do your own thing.”

Six years later however, Insecure proved it could stand on its own, with its legacy and impact immeasurable to its many Black core fans.

The show’s final season began airing on October 24, 2021, and Black Twitter’s commentary was soaked in nostalgia, joy, and hella fan appreciation. After each episode, fans of the show pondered what the concluding narratives of our favourite characters would be. Undoubtedly the most anticipated question on everybody's mind was, would Issa and Lawrence finally have their happy ending, or would they go their separate ways?

Lawrence and Issa’s relationship, romantically and sometimes platonically, has long been a contested issue amongst viewers, sprouting support groups to applaud each character’s wins and sympathise with their faults when warranted. Martin Lawrence Walker, commonly known as Lawrence on the show, has amassed an active stan-dom, ‘Lawrence Hive’ or ‘Team Lawrence,’ and I am sheepishly one of its members.

From the beginning, I never understood the hate that Lawrence got, as I knew that the writers were being intentional with his character arc. While his passive tendencies make me eye-roll habitually, as a Black cis-woman viewer, his complexities offered a glance into the performance of Black masculinity.

Most evidently, Insecure’s depiction of Black male characters was conscientious and refreshing, often providing their Black male leads with multi-dimensional arcs ranging from love, infidelity, and mental illness.

Black representation in American media has a long and distorted history. Media consumption and portrayals have served as a looking glass, reflective of society's ideals and expectations. In the West, they serve as gateways to preserve capitalism, patriarchy, and White supremacy. As Bell Hooks puts it, “opening a magazine or a book, turning on a television set, watching a film, or looking at photographs in public spaces, we are most likely to see images of Black people that reinforce and re-inscribe White supremacy.”

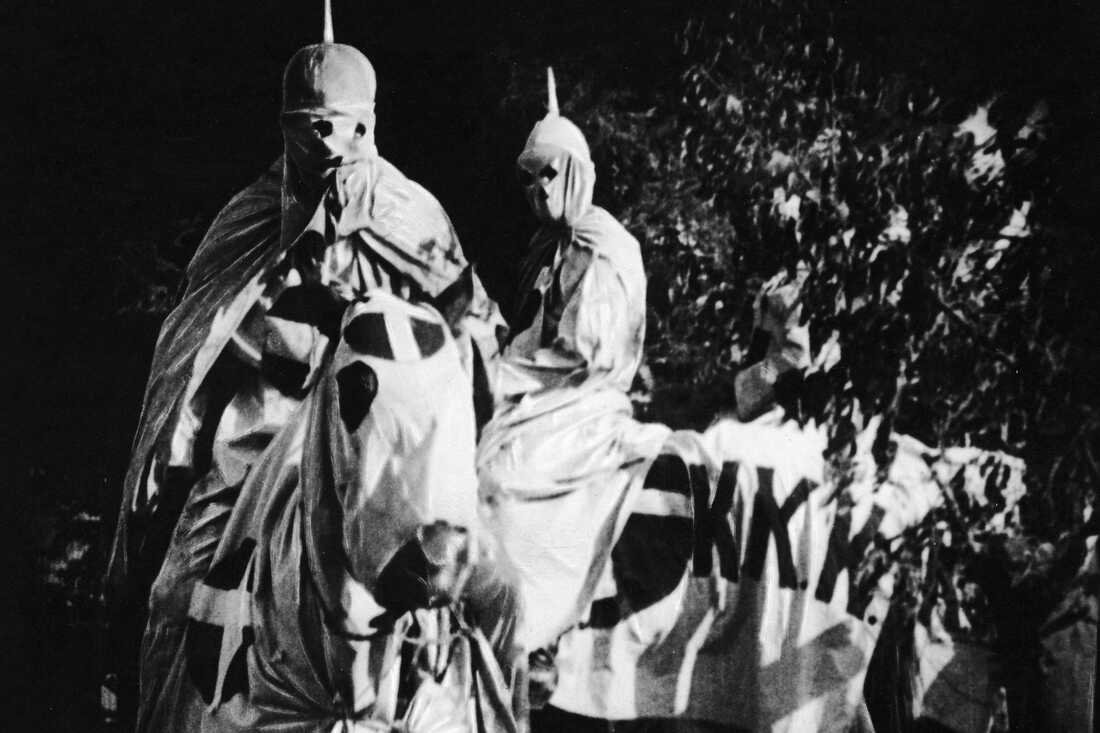

In 1915, D.W Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was released, becoming America’s first blockbuster film and pop culture moment. It was a silent film set in Antebellum South during the Reconstruction Era. Featuring White actors in Blackface, it pushed egregious stereotypes of Black Americans, and specifically Black men, as animalistic buffoons and rapists who are a threat to White women and their purity.

Still image from Birth of a Nation, 1915

Black characters up until the end of the 1960s played roles solely in subservient and comedic spheres, pandering to the White gaze; and when Black actors, actresses, and creators finally took centre stage in the early 1970s, the period marked the emergence of Blaxploitation. A portmanteau of ‘Black’ and ‘exploitation’, Junius Griffin and the NAACP coined the term to describe the genre’s violent and criminal portrayal of Black Americans, as well as its misrepresentation of the Black Panther Party and Black Liberation as a whole.

White supremacy has permitted Black men and boys to be exposed to intense amounts of violence and trauma in their physical lives, including when they flip through TV channels or scroll through the internet. Stereotypes in the media have labeled them as angry and threatening, only able to receive salvation through the aid of White hands. When amplified, these racist tropes perpetuate and normalise bodily harm towards Black boys. In covert forms such as premature deaths through homicide or suicide, or on a mass scale through mass incarceration.

When we are first introduced to Lawrence in Insecure, he’s jobless, depressed, and not a great partner to Issa. In his initial dialogue with the audience, Lawrence is already doing the opposite of confining to the quintessential archetype of Black masculinity: the role of provider and protector.

Black masculinity, shaped by chattel slavery and racism, is the intersection of masculine entitlement and devalued Blackness. Viewed as subordinate to White masculinity, Black masculinity is delineated in pop culture to largely one single narrative. This narrative objectifies Black male bodies as hyper-sexual and just for labour, detaches Black men from any emotional human responses other than anger and belligerence, and ignores social and economical inequalities to underscore their academic and employment opportunities in comparison to their White male counterparts.

Laid off from his job a few years back, having trouble getting his app launched, and ultimately comparing his lackluster career to that of friends, Lawrence is down bad. Issa is inferred to be the lone breadwinner within their relationship, trying her best to support Lawrence emotionally, physically, and financially. During the early first episodes fan consensus on Lawrence was not good, with many excusing Issa’s cheating with Daniel later on in the season due to Lawrence’s bum behaviour and inability to provide.

To me however, such opinions were narrow-minded. Insecure’s depiction of Lawrence’s depression was gentle, offering a perspective on Black mental health that handled Black men with care, unlike other contemporaries. In Lawrence’s depressive state, we saw his relatable vulnerability, his mental illness manifesting his neglect of hygiene, life, and him being a solid partner to Issa. Even arguments about Lawrence not providing fell flat to me, as they reinforced ideals of the performance of Black masculinity and White patriarchy.

Within the patriarchal structures we exist in, men are assigned roles of provider and protector, rather than encouraged to share responsibilities with their partners.

Fighting for their physical survival in a state that has systematically acquired their lives through the prison-industrial complex, Black men struggle in gaining true economic independence. Through this system, people of colour, especially Black men, are incarcerated at disproportionately higher rates than White people, proving beneficial for governments and corporations invested in the scheme.

From a CEPR study, Black men have had the highest unemployment rate of all races for the past 20 years. In another earlier study from 1996, economist Harry J. Holzer underscored with survey data, “Black men receive fewer job offers than any other race/gender group as job applicants, especially in the lower-wage service sector.”

So why must we perceive them as providers and protectors of Black women, the Black household, and ultimately the Black community, when they can’t even save themselves?

Slavery cemented Black males as submissive, simple-minded, servants to the White gaze. Proned to violent sexual outbursts especially towards White women, capitalism commodified and devalued their bodies strictly for labor.

In Season 2 Episode 4, Lawrence meets two women at a grocery store, one White and the other Asian. Before making it over to the store, Lawrence is pulled over by the police. The stop is ultimately nonviolent, but foreshadows a heavier theme throughout the episode.

Lawrence, still in his problematic fuckboy phase, has a threesome with the two women. The whole scene is cringy since it’s clear to the viewers these two women only see Lawrence as a fetish, but Lawrence seems into it up until he is unable to sexually satisfy the second woman. It's only when they sulk and shit on him, clearly disappointed that he Lawrence has not lived up to the sexual deviant image of Black men that he gets it, that he is crushed.

Lawrence later calls his friend, still clearly emotionally conflicted from the incident, but again performative masculinity checks in. Lawrence and his friend hail the encounter, and Lawrence drives off from Issa's apartment without going inside. Scenes like this are littered throughout Lawrence’s arc in the show, accentuating the dichotomy between Black men, capitalism, and White supremacy. In one episode, we can see Black men as imminent threats through Lawrence being pulled over by the cop, and in another just a sexual conquest from the non-Black women.

Insecure is attentive and mindful of Lawrence’s insecurity and societal pressures, while also deliberate in calling out his misogyny. While Lawrence suffers from performing Black masculinity, he can be deliberately misogynistic in the way he compartmentalised the women in his life. Longing that they make him feel special and valuable, Lawrence is not always able to reciprocate the same care, sometimes unintentionally hurting the women around him.

Seasons 2 and 3 saw both Issa and Lawrence enter their respective ‘hoe phases’ after their uncoupling, but it’s clear who benefits more from heteronormative hookup culture. Lawrence has a bevy of women he sleeps with, to the point where it's nauseating to watch. With each of these encounters, he’s able to avoid any real emotional intimacy he craves, but can’t seem to adequately achieve.

Because the patriarchy rewards men for their lack of emotional landscape, Lawrence can, and does, excel at casual sex. Issa on the other hand, stumbles badly in her hoe-rotation, poignantly in her friends with benefits situation-ship with Daniel.

Lawrence’s ups and downs throughout this show don’t exactly show him to be a good person, but they ultimately show him to be a complex person, highlighting the many ways in which we can grow from our lowest moments.

It’s clear while watching Insecure, that Issa Rae and the show’s cohort of writers were aware of cliche tropes constantly associated with Black men in media and society. Through the series, the complexity of Black masculinity was scrutinised, providing space for a more nuanced discussion on the topic, but most importantly a possible refuge for its Black male-identifying viewers.

The dichotomy of Lawrence and Issa’s separate lives before their eventual coupling in the last season also serves to underscore the very real issues Black men and women face in our world today. At its core, Insecure teaches us to celebrate authentic and complicated Black love stories.